Town's housing chief calls time on a 33-year career move

Wednesday, 21st April 2010.

Haverhill-UK’s David Hart, who was a junior reporter in the town when Mr Cook arrived, has been talking to him about his career and about the dramatic and continuing changes in housing provision in Haverhill they have both seen since that time.

********

In 1977, three-quarters of the housing in Haverhill was council-owned, about one per cent private sector renting and the rest privately owned. In most of the UK the balance was the reverse of that – as it is in Haverhill now – which made the town an interesting challenge for a new housing officer.

Steve Cook admits he came here from the Cotswolds as a career move. He wanted to manage an office of his own, and intended to stay a couple of years. But a combination of personal circumstances and the way the then recently-formed St Edmundsbury Council operated kept him here.

In many ways a town development town – Haverhill had gone through massive expansion as a London overspill town in the previous 20 years – was an ideal place for a man whose interest in housing stemmed from a very particular and life-changing moment, one that he shared with many of his generation.

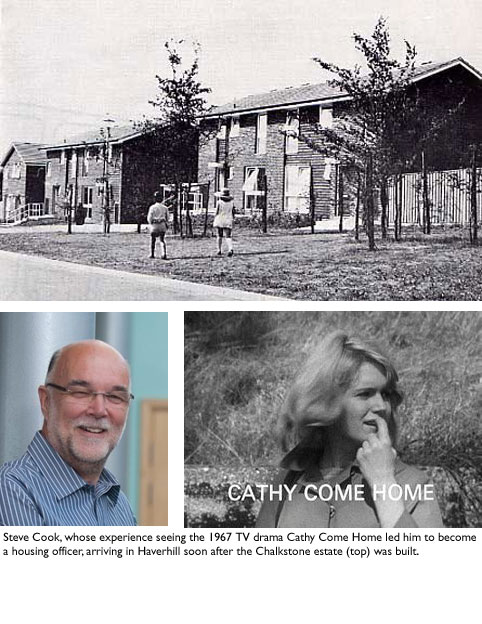

“I had left school in 1966 without any intention of going on to further education and was looking for a job,” he said. “I tried a couple of things that didn’t work out and I came home and sat down one evening and Cathy Come Home was on the box – and that was it.”

Cathy Come Home was an iconic BBC television drama directed by Ken Loach which highlighted homelessness and led to massive support for the recently-formed charity Shelter, and eventually to the Homeless Persons Act of 1977.

In Haverhill, Mr Cook was able to house engaged couples virtually straightaway, because there was so much housing available. “I came from a place of high demand and low turnover to the complete opposite,” he said.

“It was a fantastic opportunity for me. I had a complete team to work with, I was 20 miles from base, my own boss and given the opportunity to get on with it. And I was allocated a house in Vetch Walk to begin with – a three-bedroom house for a single man. Imagine that.

“I remember Haverhill being quite deserted at the weekends in those days as so many people went back to London to see their families. There was an interesting dynamic between the indigenous population and the incomers.

“The town now had a grand plan under the Gibberd design, and people were coming to a new town, a new job and a new start. Unfortunately, not as much thought had been given to the social dynamics of the situation as we would do these days.”

Also, although it was not immediately apparent, Haverhill’s big expansion was running out of steam. The Arab oil crisis affected the economy and industries left or downsized just when Haverhill needed investment.

“The mix of tenures was out of kilter with the rest of the UK, as was the age profile,” said Mr Cook. “I think the average age was about 30. A lot of jobs were unskilled or semi-skilled and offered limited opportunities.”

The housing plans of the London County Council (LCC), later the Greater London Council (GLC) did not address the needs of the town, and provided almost exclusively family housing. Out of the 1,000 houses which made up the new Chalkstone estate in the early 1970s, there were just 15 one-bedroom flats.

With high unemployment (about 11 per cent) in Haverhill, St Edmundsbury had to put a lot of effort into bringing firms to Haverhill, and the system of key-worker housing was an important element of that.

Eventually the economy did lift and then Mr Cook was faced with a waiting list which enabled the council to take back the 100 homes on the Chimswell estate which had been let to USAAF personnel from Lakenheath.

In 1984 Mr Cook moved from the Haverhill offices to a more senior post in Bury St Edmunds. His job was taken over by Karen Mayhew, with whom he has worked ever since, and who will take over from him as chief executive of Havebury.

By 1987 he was chief housing officer for the whole of St Edmundsbury, and in 1995 became director of environmental health and housing. He was given the opportunity to get involved at a national level on the Chartered Institute of Housing, and was a housing policy adviser to the Local Government Association, at the cutting edge of the latest thinking and able to influence policy nationally.

In his new joint role he saw how the health and housing agendas were linked. “People who have poor housing don’t generally have good health,” he said. “I came more and more to recognise the importance of this.”

But an even bigger change was on the way. In the mid 1990s the council was keen to improve its homes across the borough, but income from investments was falling and there was a downward pressure on council tax. Capital projects had to be cut back.

By 1999 it was clear there was a huge funding gap. Just replacing the central heating in 6,500 homes would cost millions. Along with the tenants forum the council had formed, it began to look at options.

“It was never a political issue,” said Mr Cook. “It was always about what was best for the tenants.” After nearly two years the decision was made to transfer the housing stock to a specially formed, not-for-profit housing association, which was called Havebury.

In June 2002 the council received £46m in all, and the tenants suddenly began to see the long-awaited improvements. All the improvement programmes restarted.

“Since then we have done 20,000 improvements and spent £59million, but there is still some to do,” said Mr Cook.

He became chief executive of the ‘shadow’ Havebury in 2001, and of the real thing as soon as it swung into action. Far from being daunted at being cast adrift from a local government job into the private sector, Mr Cook was excited by the prospect.

“Straightaway I moved from saying no all the time when people asked for improvements, to being able to say yes – most of the time.”

Now he is on the regional executive committee of the National Housing Federation, the representative body for 1,200 housing associations in the UK.

“I suppose the biggest change in 30-odd years is that we have moved from being a housing service which said this is what you’ll get to one which is highly-focused on what tenants need,” he said.

“Before transfer 79 per cent of tenants were satisfied with the service, now it’s 92 per cent, compared with a UK average of 85 per cent.

“There has also been a change in the nature of the people we are delivering services to. There is a far larger number of older people and people with other vulnerabilities. The future is in sustaining people in their homes, and we have to deliver a service to allow that to happen.”

He points to the complete conversion of Horace Eves Close in Haverhill which is currently going on.

Another big change came in the wake of the right to buy legislation of the 1980s. Initially it depleted the stock and, as expected, the best houses went first. “But it has enriched the mix,” he said. “We have not got monolithic blocks of council housing estates. Chalkstone is 50 per cent owner-occupied or private renting now. It used to be 3.5 per cent.”

But he has a warning for the future. “We are still not going to be able to address the total need,” he said. “A number of properties are still needed of all kinds. People will rue the day 40 years down the road if they don’t allow development.”

Havebury now has 1,800 homes in Haverhill and in the last seven years has invested £25million in the town – private sector money which would not have come in otherwise. A lot of that has been spent with local businesses.

“When I set out my aim was to be a housing manager,” said Mr Cook. “I progressed to become director of housing, but then, because tenants put their trust in the housing team who had run the service, my ambition led me to become chief executive of a housing association. But still I am most proud of seeing so many people housed in good quality homes.

“I arrived in Haverhill not knowing what to expect and I found a gritty and strong community which many from outside still under-rate. It’s got a great future and I hope what I have done over the years will be a contribution towards that future success.

“I feel I am leaving at the top of my game. We have taken customer service in this organisation to a new level, created some award-winning housing and made sure that tenants’ voices are heard.

“In the last 12 months we have housed 600 households, which is double the normal. We are giving people a life opportunity – and that stems right back to Cathy Come Home.”

Comment on this story

[board listing] [login] [register]

You must be logged in to post messages. (login now)